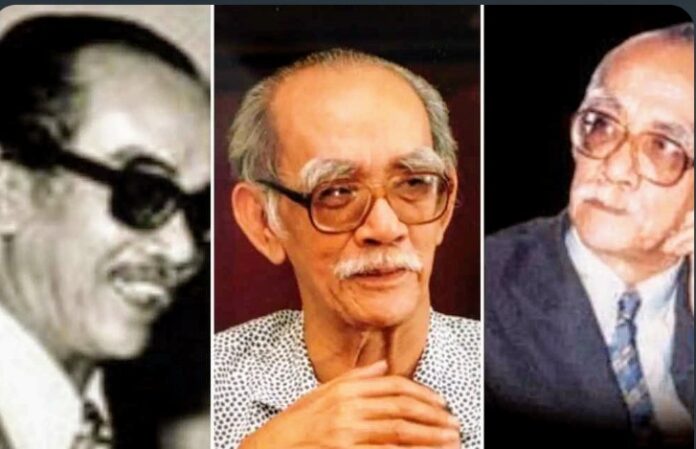

Tan Sri Abdul Samad Ismail, born a century ago on April 18, was a genuine nationalist and an intellectual ahead of his time.

A master of his craft, making monumental contributions to journalism, politics and literature.

By Frankie D’ Cruz

PETALING JAYA: The fearless Malaysian journalist A Samad Ismail, born a century ago on April 18, had the courage of an army. He had that most useful piece of equipment required of editors – a backbone.

It kept him upright through three periods of detention under the Internal Security Act – twice by the British in colonial Singapore and once in Malaysia

Samad was an intellectual ahead of his time, and an influential leader in journalism and literature. He had a great sense of nationalism and a desire to free the Malays from poverty and ignorance.

Pak Samad, as he was known in the newsroom, was Malaysia’s first journalism laureate, and is still considered by many to represent the high-water mark of what serious-minded, challenging journalism can and should be.

On April 21, a centenary remembrance on “The Man Behind the Enigma”, will pay tribute to the man who inspired writers and politicians in Malaysia and Singapore.

The event at Gerakbudaya (2, Jalan 11/2, Petaling Jaya) at 3pm will feature as speakers the constitutional lawyer Dominic Puthucheary, former senator and retired professor Syed Husin Ali and veteran journalist Terence Netto.

Utusan and Japanese invaders

A Samad Ismail with arm on hip next to a Japanese officer (top left of picture) visiting an anti-aircraft defence unit of the Giyu Gun in Singapore during the Japanese Occupation. (From A Samad Ismail: Journalism and Politics)

Netto said Samad occupied one of the best vantage points in history, plunging into journalism and politics in the 1940s, when “the world was in ferment and Southeast Asia was rife with anti-colonial sentiment”.

Born in Geylang in Singapore in 1924, Samad was the eighth child in a Javanese family of 13 children. After completing his schooling by passing the Senior Cambridge examination at the age of 16, Samad’s headmaster father steered his precocious son into becoming a journalist with the newly set-up Utusan Melayu newspaper, which became the platform of Malay nationalism.

Samad learned his trade under the tutelage of Rahim Kajai, who is regarded as the father of Malay journalism, and picking up the tricks of the trade in the year before Singapore was invaded by the marauding Imperial Japanese Army.

Netto said: “They say you learn to swim better when pushed into the deep end. The deep end was where Samad found himself by the time the Japanese took over Utusan and turned it into Berita Malai.

Making of a journalist.

“Samad learned fast and though still in his late teens, he learned at first hand the ground rules that go in making a good journalist.

“He developed the traits of a good journalist through curiosity, disdain for presumptions, respect for those who can deliver (meritocracy), and the inexhaustible interestingness of what seemingly is the ordinary face of life.”

These qualities combined with an innate independence of mind and a voracious appetite for reading the works of thinkers and writers whose ideas have moved humankind, Netto said.

“Samad became imbued with nationalism and a desire to free the Malays from poverty and ignorance. But there was never a parochial tinge to his strivings to free Singapore and Malaya from colonial rule,” he said.

Despite intrusions into the political realm in Singapore in November 1954, he resolutely kept his practice of journalism intact with Utusan Melayu.

The NST years.

Netto said Samad’s fidelity to the essentials of his craft was evident in the early 1970s when he had charge of the editorial department in the New Straits Times, which despite being owned by business interests aligned to Umno provided scope for the political management of the news.

“Samad weaved skilfully, to the extent it was feasible, to deflect this management, to adhere to the canons of the trade. Even within a circumscribed arena, he was able to demonstrate that independence of mind that was his hallmark.

“No journalist in Malaysia and in Singapore managed this freedom of manoeuvre better than Samad,” said Netto. “That was why he gained the admiration of good journalists who worked under him, not the hacks, and they have maintained their high regard for him,” he said.

Although Samad is hardly mentioned today, the few journalists who remember him from having worked under him and admired his devotion to canons of the occupation, hail him as a titan of the profession.

“He died at the age of 84, some 16 years ago and is largely forgotten. But so long as there are people who have read his journalism and are aware of the conditions within which he forged his trade, he will be regarded as one of the giants of journalism,” Netto said.

Genuine nationalist, intellectual

From the time he became a journalist in Utusan Melayu in 1939 until his retirement in 1988 from NST, Samad had run the gamut of labels that allies and adversaries attempted to fix on him.

Netto said: “Acclaimed a nationalist of the first rank and detained as a communist for sinister plotting, Samad had been through a welter of experience not likely to be replicated in one life.”

“The reasons for this are obvious: the accidents of both time and place contrived to have him present at epochal events in the intertwined histories of two countries (Malaysia and Singapore).”

Journalism, politics and literature.

A Samad Ismail with Prince Norodom Sihanouk (centre) who hosted talks between Tunku Abdul Rahman (left) and President Macapagal in Phnom Penh to improve strained relations between Malaysia and the Philippines. (From A Samad Ismail: Journalism and Politics)

He was a pioneering journalist (Utusan Melayu), conduit for the Indonesian revolution (1945-49), midwife at the birth of a newspaper (Berita Harian in 1958), and the rebranding of another (NST in 1972).

In politics, he was political party convenor (People’s Action Party in 1954), speechwriter to one prime minister (Abdul Razak Hussain, 1970-76), and a deputy prime minister (Dr Ismail Abdul Rahman, 1970-73).

As founder of the Asas 50 literary movement, he set new standards in intellectual alertness, moral tenacity, wide-ranging curiosity and the strength of his political conviction.

Netto said: “Samad fused the strands of journalism and politics, arts and quixotic adventure, as few in the Southeast Asian region had done.

“Long suspected as a radical and for that reason kept at a wary length by those who tapped him for advice, the theories of Marx may have been the premise of Samad’s life, not necessarily its conclusions.

“Samad had to a remarkable degree what T S Eliot called an ‘experiencing nature’. Such a nature is apt to submit ideological preferences to tests in the school of hard knocks.

“In that rough and tumble, few things wither faster than false premises. He was in Antonio Gramsci’s description an ‘organic intellectual’, one who allows the messages of his environment to mould and form his ideational content.

No communist, Mr Lee.

“For that reason, Samad could not have been a member of the communist party, as his adversary Lee Kuan Yew claimed Samad said he was,” said Netto.

“He had an undogmatic mind,” said senior constitutional lawyer Dominic Puthucheary to Netto when drawn on the subject. “If he had been a member of the Communist Party of Malaya, they would have had to throw him out,” Dominic averred.

Dominic knew Samad in Singapore in the 1950s when Samad and Dominic’s elder brother James were collaborators in the formation of the PAP in 1954. Both subsequently disagreed with Kuan Yew, the secretary- general of the party, and went separate ways.

A promise that withered.

Boyhood chums A Samad Ismail (right) and Devan Nair leaving CID headquarters in Singapore on their release from detention in 1953. (From A Samad Ismail: Journalism and Politics)

These matters would culminate fatefully for Samad in June 1976 when he was detained under the ISA, for the third time in his life.

Samad was then managing editor of NST and about to be elevated to group editor and was in the process of assembling an experienced and skilled team of journalists to drive the stable of English-language and Bahasa Malaysia newspapers to a preeminent place in Malaysia.

“That world was never to recover the promise it held on the eve of Samad’s detention,” said Netto.

Editor: This article had appeared in the Free Malaysia Today